Chronologically, my experience with wildlife science started in 2005, when I began volunteering my time as a wildlife rehabber for a local veterinarian. People would bring injured or orphaned birds to the vet, who would in turn hand them over to the volunteer rehabbers. It was our job to take care of them until they were ready to be released back into the wild. I would continue to use my summers to seek out opportunities to work with animals. In 2008 I volunteered as a naturalist at Oxley Nature Center. The following summer, I worked as an intern at the Tulsa Zoo.

Chronologically, my experience with wildlife science started in 2005, when I began volunteering my time as a wildlife rehabber for a local veterinarian. People would bring injured or orphaned birds to the vet, who would in turn hand them over to the volunteer rehabbers. It was our job to take care of them until they were ready to be released back into the wild. I would continue to use my summers to seek out opportunities to work with animals. In 2008 I volunteered as a naturalist at Oxley Nature Center. The following summer, I worked as an intern at the Tulsa Zoo.

This general interest in wild animals carried over into my focus as an undergrad. In 2011 I graduated from Oklahoma State University, where I majored in Wildlife Ecology, with a minor in Zoology. For my honors thesis, I measured the autumnal attrition of scissor-tailed flycatchers as they flew south for their winter migration.

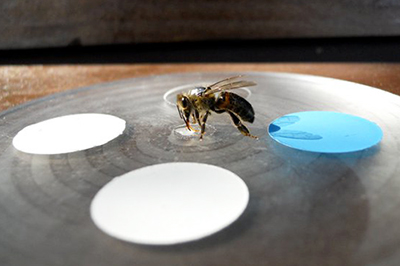

While a student at OSU, I started to develop an interest in animal behavior, and I was accepted into a Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) program sponsored by the University of Central Oklahoma. As part of that program, I spent two months of 2010 in Turkey and Greece studying the behavior and intelligence of European honeybees. By training the bees to seek out certain color patterns, we were able to determine that honeybees can remember and avoid specific arrangements. I thought that was quite impressive considering that honeybees have a brain the size of a sesame seed.

While a student at OSU, I started to develop an interest in animal behavior, and I was accepted into a Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) program sponsored by the University of Central Oklahoma. As part of that program, I spent two months of 2010 in Turkey and Greece studying the behavior and intelligence of European honeybees. By training the bees to seek out certain color patterns, we were able to determine that honeybees can remember and avoid specific arrangements. I thought that was quite impressive considering that honeybees have a brain the size of a sesame seed.

After I graduated from OSU, I began working as a research assistant for Dr. Alex Ophir, whose lab studies the social behavior of Prairie voles. Prairie voles are interesting to scientists because they are one of the few species of mammals that practice monogamy. My responsibilities included day-to-day animal care, updating the colony database, monitoring and assisting with the graduate student’s experiments, and training undergraduates to properly handle the voles. I even devised and performed my own experiment designed to examine the spatial and social memory of male prairie voles. Oddly, the accomplishment I’m most proud of from my time in the Ophir lab would be creating the “PR voles”. Ordinarily, voles are terrified of people and don’t like being held or handled (everybody in the lab had been bitten at some point). I managed to train a trio of males to overcome their fear of people. From that point on, anytime anyone in the lab needed a vole for a photo or public outreach, they’d use my trained PR voles.

After I graduated from OSU, I began working as a research assistant for Dr. Alex Ophir, whose lab studies the social behavior of Prairie voles. Prairie voles are interesting to scientists because they are one of the few species of mammals that practice monogamy. My responsibilities included day-to-day animal care, updating the colony database, monitoring and assisting with the graduate student’s experiments, and training undergraduates to properly handle the voles. I even devised and performed my own experiment designed to examine the spatial and social memory of male prairie voles. Oddly, the accomplishment I’m most proud of from my time in the Ophir lab would be creating the “PR voles”. Ordinarily, voles are terrified of people and don’t like being held or handled (everybody in the lab had been bitten at some point). I managed to train a trio of males to overcome their fear of people. From that point on, anytime anyone in the lab needed a vole for a photo or public outreach, they’d use my trained PR voles.

Soon after leaving the Ophir lab, I had the opportunity to apply my education in science to a profession often overlooked; science education. In 2012, I became a science teacher for Tulsa Public Schools. I earned my teaching certification in both chemistry and biology, and taught both high school chemistry and junior high physical science. I remember those two years as a science teacher as being highly stressful, but also incredibly rewarding. Nothing really compares to the privilege and responsibility of shaping the future of >130 kids. Because of that experience, I have gained a profound respect for those people with the immensely difficult (and often thankless) task of teaching children in a society that undervalues education.

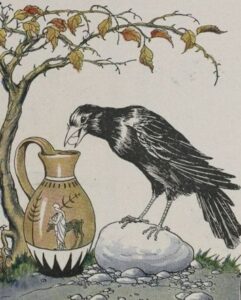

I joined the Marzluff lab at the University of Washington in 2014, where I spent the next seven(!) years working as a graduate student. In addition to attending classes, I also spent my time studying the behavior of wild crows (both in their natural environment and in an aviary). I recorded the calls they gave around piles of food, tested their ability to solve a string-pull task, examined their brain activity in response to hearing other crow calls and/or seeing food, and trained them to use stone tools (I modeled that experiment after the Aesop fable “the crow and the pitcher”).

I joined the Marzluff lab at the University of Washington in 2014, where I spent the next seven(!) years working as a graduate student. In addition to attending classes, I also spent my time studying the behavior of wild crows (both in their natural environment and in an aviary). I recorded the calls they gave around piles of food, tested their ability to solve a string-pull task, examined their brain activity in response to hearing other crow calls and/or seeing food, and trained them to use stone tools (I modeled that experiment after the Aesop fable “the crow and the pitcher”).

I currently work as an instructor for the Psych Department at the University of Washington, where I specialize in classes focusing on animal behavior.